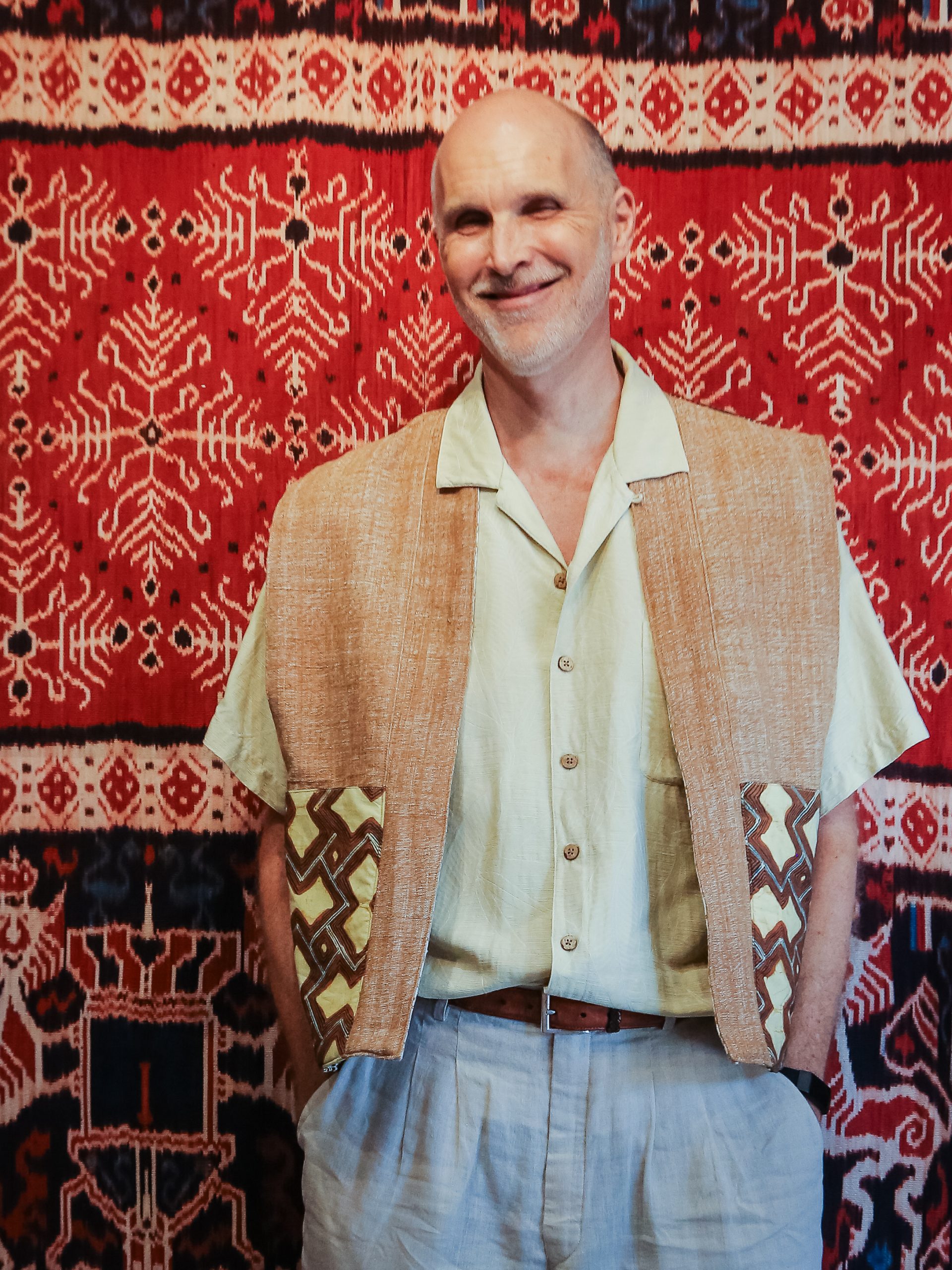

To empower women is to empower society—this is what William Ingram had in mind when he co-founded Threads of Life 28 years ago. William and his wife Jean, along with their friend Made Pung, initially offered a tour service to the Indonesian islands of Bali, Timor, Flores, Sumba, and the surrounding areas. One of the material culture items offered by the communities were textiles woven using traditional backstrap looms and dyed with natural dyes like indigo, Morinda, and mud. In places like East Nusa Tenggara, traditional woven textiles are important to the community — not only because they have a marketable value that can help meet a community’s economic needs, but also because of their importance to cultural preservation efforts. William, with a background in community development, saw both potential and crisis looming before his eyes.

Behind this potential, William encountered two challenges. First, the intergenerational loss of knowledge regarding local wisdom of weaving techniques and traditional dyes. Second, the changing landscape where the raw materials for natural dyes usually grow. For these reasons, William felt that something needed to be done so that the artisans —who are almost all women— could continue doing what they love. Threads of Life is the answer to this challenge.

In the early years, it was certainly not easy for Threads of Life to develop itself. Not to mention, in its early years, around 1997-1998, the monetary crisis hit Southeast Asia, with Indonesia feeling the most severe impact. Furthermore, the business environment at the time was still very difficult because Indonesia was under the New Order regime. However, Threads of Life managed to maintain its business amidst these challenges. Not only that, they thrived even further.

Today, Threads of Life has expanded its reach beyond Bali, Timor, Flores, and Sumba—they now source products from Java, Kalimantan, Lembata, Savu & Rai Jua, and Sulawesi. To date, they sell more than 10 types of products ranging from cushions to shawls. In addition to selling products, Threads of Life also provides a variety of services and activities. They provide textile dyeing services and also hold numerous workshops and textile dyeing classes for the public. Due to its growth, Threads of Life has made a significant impact. They have empowered more than 1,200 weavers from 35 groups across 12 islands in Indonesia, making a difference in the economy of the women weavers. The most obvious impacts of this improved economic welfare have been more years of schooling for the children and housing repairs.

Threads of Life upholds a set of values, which are supporting women, building livelihoods, revitalizing traditions, and conserving dye plant ecologies. Although their main business model is selling textile products, Threads of Life leaves production to the weavers —because weavers have their own methods, seasons, and quality control methods established since the time of their ancestors. Threads of Life is always looking for new weaving communities and rather than asking weavers to follow market trends, asks them these questions: What motifs can they make? What did their mothers, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers make? What do they consider makes for a good textile within their tradition?

For example, Threads of Life adjusts to the production time of each woven fabric. When the planting season arrives, weavers typically focus on agriculture, so production temporarily stops. Besides respecting their primary livelihood, weaving during the rainy season with its high humidity can damage the fabric’s pattern. Vegetation for indigo dye is harvestable from March to May, and the Morinda red dye requires a time-consuming oiling process. Therefore, a single woven fabric measuring approximately 2 meters and using two colors can take up to 1.5 years to produce.

The richness of artisanship Threads of Life has developed aligns with Pable’s values, which is part of the reason why Threads of Life wanted to incorporate Pable’s fabrics into their designs back in the early days of Pable. William also wanted to add a story to each product, and Pable’s story of sustainability and circularity fell right into place.